Cal. Veh. Code SS 27001.

To my horror, the Ninth Circuit panel has just voted to reject an First Amendment challenge against this draconian law.

California law provides that:

>

Each motor vehicle must be equipped with a working bell, gong or horn or whistle, or any other device that can emit a loud, abrupt sound to warn pedestrians, animal riders, drivers, and persons boarding or exiting street, interurban or railroad cars. It is illegal to use a bell, gong or horn for any other purpose than warning others of danger.

>

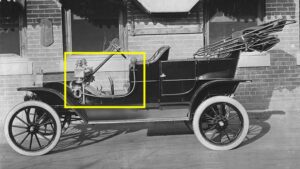

Sorry, this was the 1913 original. This was five years after Ford introduced the Model T. The Model T was a revolutionary vehicle, affordable, easy to use, and durable. It has left an everlasting legacy. Ford Motor Company is my client and I am not aware of any Model T-related litigation. It had many features that were new for its time. (Same) And as you can see it came with an horn. I assume that California was overrun from 1908 to 1913 by inferior vehicles without such a device. I believe or would like to believe that some vehicles after 1913 were equipped with large gongs capable of producing a loud, jarring sound to warn of the approaching vehicle.

The statute says that:

>

The driver must use his horn to give an audible alert when it is reasonable for the vehicle's safe operation.

(b) Except as an alarm system for theft, the horn may not be used in any other way.

>

Cal. Civ. Code SS3537 ("Superfluity doesn't vitiate "))," but it does not mention gongs or bells anymore, only boring old horns. It is important to note that it says the horn may only be used when "reasonably necessary" to ensure safe operation.

What if I wanted to use it for communication?

Susan Porter, a member of a protest outside a government building in 2017, allegedly violated this law by using her horn. According to the opinion, Susan Porter "honked her horn three times in a row, for a total 14 beeps" as she drove away from a protest (of which she was formerly a part).

Unsurprisingly, the local deputy sheriff heard one or more beeps and acted immediately. He cited Porter bravely for misusing a vehicle's horn, as per section 27001. He did not appear at her hearing and the citation was thrown out. Porter, perhaps suspecting that deputy's actions were more than a neutral effort to protect the local community from malicious and willful tooting, sued, arguing that the law was unconstitutional.

Porter's standing to file this suit was the first question. In federal court, "standing" is required to show a concrete injury. Porter stated that she no longer uses her horn to express herself out of fear of a citation. This "self-censorship," as long as it is "well founded", is sufficient. The State argued Porter did not meet her burden of proof because she "had not shown a plan for expressive honking in the future" and that almost no one is cited for violating Section 27001. It would be interesting to see a concrete plan for "expressive honking." But the court found that Porter still had standing without it. Let's move on to the First Amendment.

I was glad to see that there was no disagreement about the fact that honking at least in some cases is "expressive behavior" to which First Amendment can apply. You already know this. Washington Horn-Honker wins First Amendment Challenge (Oct. 27 2011). It may be that it depends on the situation, but Porter's honks were clear. The Ninth Circuit, again disappointing me, wrote that "even though we do not define the full scope today of expressive honking," it held that "enough honks" will be understood within context to treat Section 27,001 as prohibiting certain expressive conduct.

Porter argued that the law was unconstitutional, because it is a "content based regulation" which must be scrutinized closely. It's only valid if the law is "least restrictive" in order to advance a "compelling interest of government". Laws fail this test almost every time. The State said that it was "content-neutral," meaning it only needed to be "narrowly tailored", to advance a "significant interest of the government" (the "intermediate examination" test). It is often a matter of which test to use, as it was in this case.

Porter claimed that honking is an expression. The court ruled that it didn't really matter. The court ruled that the law does not distinguish between honk messages. It "prohibits any driver-initiated use of horns" which isn't essential to safe operation. The law does not distinguish between "political, ideological, celebratory, or summoning a carpool driver" (yes, if summon-honking in California is a crime). The law does not discriminate on the basis of content.

It's not surprising that the court found that traffic safety is a "significant interest" of government. But, does this law have a "narrowly tailored purpose" to achieve it? The court ruled that it was, noting that the government does not have to use "the least restrictive means" under intermediate scrutiny. But this law bans all expressive honking. It doesn't appear tailored at any point. Porter argued that California, like other states, could instead ban only honking "that disturbs the peace" and not "honk solely for safety". This would have been sufficiently tailored to exclude Porter's 14 short-beep- salute and make it so that honking for a carpool driver would not be a crime. It's possible that the Ninth Circuit has relegated its response to a footnote because it isn't very convincing. Porter's challenge was rejected.

Porter seemed to be focusing on the statute's "face" rather than "as it was applied". The court claims that this wouldn't make a difference but I am not convinced. Judge Berzon, in a long dissent -- this opinion is 60 pages and the dissent almost half that length -- agreed that intermediate scrutiny was necessary.

>

Unfortunately, I could not find any evidence to support this claim, even though Wikipedia states that the first police vehicle in the world, which was deployed by the Akron Police Department (Ohio) in 1899 and was equipped with a gong, was an electric-powered vehicle. This latter claim, however, is not well-sourced.

.png) EntertainmentCelebrityComediansAlternative News MediaFunny VideosPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions

EntertainmentCelebrityComediansAlternative News MediaFunny VideosPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions